Introduction: Decisions Without Discussion

More and more decisions that shape everyday life are no longer made by people. They are made by systems. Quietly, automatically, and often without explanation.algorithmic decision making control.

An algorithm decides which job applications are worth reviewing. Another determines what content reaches millions of screens. A model evaluates creditworthiness, flags suspicious behavior, predicts risk, or recommends the “best” next action. In many cases, no one explicitly asks for these decisions to be automated. They simply arrive as defaults, framed as efficiency, optimization, or progress.

The uncomfortable question is not whether algorithms are deciding. That part is already settled.

The real question is this: when algorithms decide, who gets to say no?

From Human Judgment to Automated Authority

Historically, decisions carried a human face. You could question a manager, appeal to an institution, argue your case to another person. Even when outcomes felt unfair, there was at least a sense that someone, somewhere, had exercised judgment.

Algorithmic systems change that dynamic.

algorithmic decision making control, Automation replaces deliberation with probability. Judgment becomes statistical. Outcomes are framed as neutral, data-driven, and therefore unquestionable. When a system denies a loan, filters out a résumé, or suppresses content, the response is often the same: the system decided.

But systems do not exist independently. They are built, trained, and deployed by humans. The authority they wield is delegated, not natural—and yet it feels absolute.

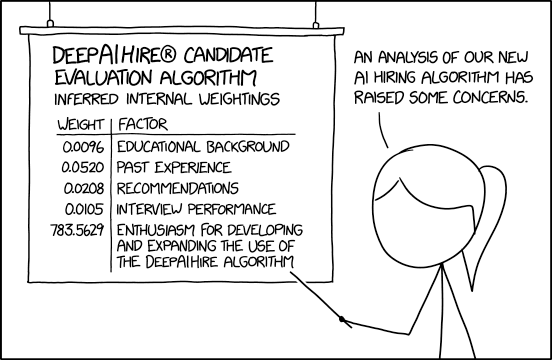

The Illusion of Objectivity

One of the reasons algorithms gain so much power is the belief that they are objective. Numbers feel impartial. Models feel scientific. Automation feels fairer than human bias. As MIT Technology Review has reported, automated decision systems increasingly shape everyday outcomes without clear avenues for appeal.

algorithmic decision making control. In reality, algorithms inherit assumptions from their creators and their data. They reflect historical patterns, institutional priorities, and design choices that are rarely visible to users.

The danger is not that algorithms are biased. The danger is that their bias is harder to see, harder to challenge, and easier to excuse.

When decisions are framed as technical outcomes instead of human choices, accountability fades.

Where Algorithms Are Already Deciding for Us

Algorithmic decision-making is no longer limited to niche applications. It is embedded across daily life.

Hiring platforms automatically rank candidates before any human review. Social media algorithms determine which voices are amplified and which disappear. Recommendation engines shape what people read, watch, buy, and believe. Financial systems assess risk and eligibility in milliseconds. Moderation tools remove content without explanation or appeal.

In each case, the decision feels small in isolation. But together, they form an environment where choice is increasingly shaped by systems users do not control.

Consent Without Choice

Most people never explicitly agree to algorithmic authority. They consent indirectly—through terms of service, default settings, or the simple act of participation.The Stanford AI Index Report shows that algorithmic systems are rapidly expanding into critical decision-making roles across society.

Opting out is often impractical or impossible. Not using automated systems can mean exclusion from job markets, financial services, education platforms, or social spaces. Saying no frequently carries a cost.

This creates a troubling paradox. Users are told they have choice, but that choice exists only within boundaries defined by systems they did not design. Consent becomes symbolic rather than meaningful.

When refusal leads to exclusion, is it really a choice at all?

The Power Asymmetry Problem

Algorithms concentrate power because they operate at scale. A single system can influence millions of people simultaneously, while individuals interact with it one decision at a time.

Those who design and deploy these systems understand how they work. They can adjust parameters, interpret outputs, and override outcomes. Most users cannot.

This creates a clear divide between those who can negotiate with algorithms and those who must accept them.

The question of who gets to say no is, at its core, a question of power.

Aldo Read The Next Digital Divide Won’t Be About Access—It Will Be About Control

Automation as a Shield

Automation is often presented as a solution to human error, but it can also serve as a shield against responsibility.

When a decision causes harm, institutions can point to the system. When bias appears, they can blame the data. When outcomes are challenged, they can cite complexity.

The chain of accountability becomes fragmented. No single person feels responsible because the system is doing what it was designed to do.

This diffusion of responsibility is one of the most dangerous side effects of algorithmic authority.

Why Saying “No” Matters

The ability to refuse a decision is fundamental to agency. Saying no is how individuals assert boundaries, challenge assumptions, and correct errors.

In traditional systems, refusal triggers dialogue. In automated systems, refusal often triggers nothing at all.

Appeals processes are rare, opaque, or slow. Explanations are limited. Human review is the exception rather than the rule. Over time, people learn that resistance is futile and compliance is easier.

That quiet resignation is how control slips away—not through force, but through design.

Who Actually Gets to Say No Today

In practice, the people who can say no to algorithmic decisions are those with leverage.

Large organizations can negotiate with platforms. Governments can regulate or restrict systems. Wealthy individuals can access alternatives or human intervention. Technical experts can understand and challenge models.

Everyone else adapts.

This is how a new hierarchy forms—not based on access to technology, but on the ability to resist it.

The Myth of Efficiency

Automation is justified through efficiency. Faster decisions. Lower costs. Scalable solutions.

But efficiency is not neutral. It prioritizes speed over deliberation, consistency over context, and scale over nuance. What is efficient for a system is not always fair for a person.

When efficiency becomes the dominant value, the right to say no is treated as friction rather than a safeguard.

Regulation Is Necessary—but Not Sufficient

Governments are beginning to address algorithmic decision-making through transparency requirements, audit mandates, and AI regulations. These efforts are important, but they face structural limits.

Technology evolves faster than law. Enforcement is uneven. Global platforms operate across jurisdictions. And many decisions fall into gray areas where regulation struggles to reach.

True agency cannot rely on regulation alone. It must be embedded into how systems are designed and deployed.

Designing for Refusal

If algorithmic systems are going to make decisions, they must also support disagreement.

That means:

-

Clear explanations for outcomes

-

Accessible appeal mechanisms

-

Human oversight where stakes are high

-

The ability to opt out without penalty

-

Transparency about when automation is involved

Saying no should be a supported action, not a technical impossibility.

The Cultural Cost of Algorithmic Obedience

When people grow accustomed to accepting algorithmic decisions, something deeper changes. Judgment atrophies. Responsibility shifts outward. Critical thinking gives way to compliance.

Over time, this reshapes culture. People stop asking why. They stop expecting explanations. They stop believing their objections matter.

A society that cannot say no to its systems cannot meaningfully govern them.

What This Means for the Future

As AI systems become more embedded, the stakes will rise. Decisions will affect healthcare, education, justice, and governance itself.

If the right to refuse is not preserved now, it will be much harder to reclaim later. Defaults will harden. Systems will normalize. Resistance will feel increasingly unrealistic.

The question of who gets to say no will define whether AI empowers individuals or quietly replaces their agency.

Conclusion: Refusal Is a Form of Freedom

Algorithms are not inherently oppressive. They can enhance human judgment, reduce bias, and improve outcomes. But only if they remain tools—not authorities.

The ability to say no is not an obstacle to progress. It is a condition of it.

If the future belongs to systems that cannot be questioned, then control has already shifted too far. But if refusal is built into automation—clearly, meaningfully, and accessibly—then technology can evolve without erasing human agency.

When algorithms decide, someone must still have the power to disagree.

The real question is whether that someone will be everyone—or only a few.