Introduction

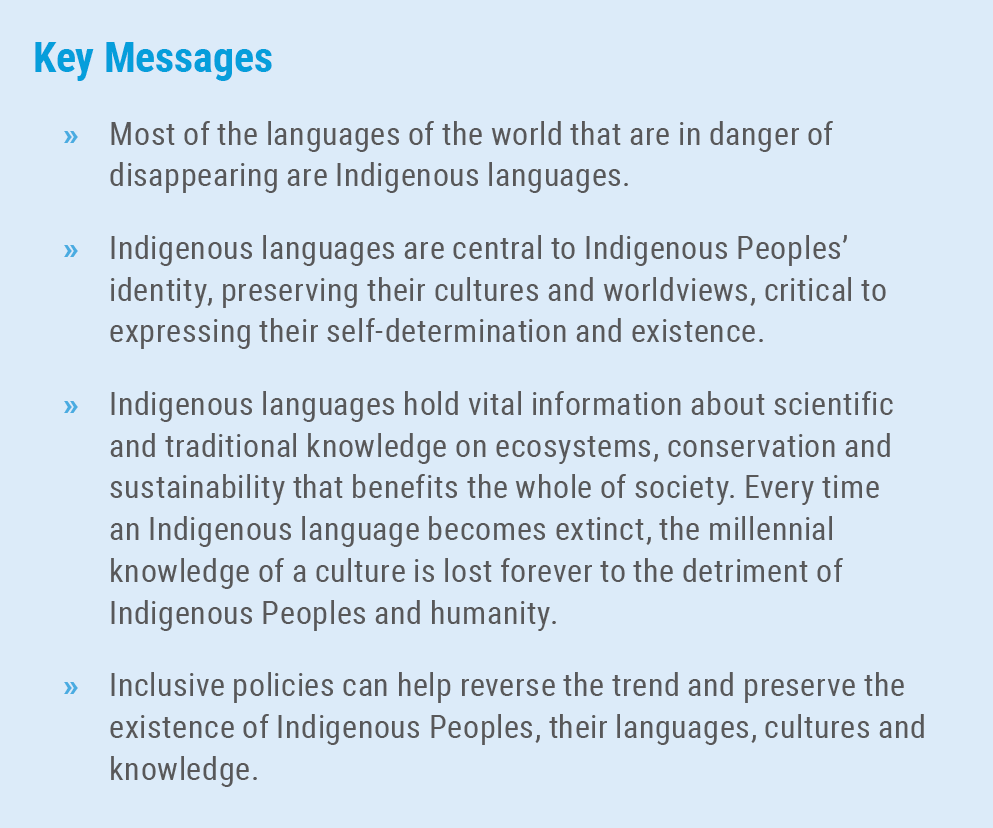

Language is one of the most powerful forces in human society. It shapes how people see the world, how they express themselves, and how they relate to others. For Indigenous peoples across the globe, language carries even deeper meaning. It represents the living connection between past and present, culture and land, ancestors and future generations. When an Indigenous language is spoken, it does far more than convey information—it sustains identity, worldview, and community.

This article explores the many ways language shapes Indigenous identity, drawing on cultural perspectives, linguistic research, and examples from Indigenous nations around the world. From worldview and ceremony to political sovereignty and resilience, language stands at the heart of Indigenous life.

1. Language as the Keeper of Worldview

Every language carries a worldview—a way of understanding reality. Linguists often call this linguistic relativity, the idea that the structure and vocabulary of a language influence how its speakers think and experience the world.

In Indigenous contexts, this influence is especially strong because language is intertwined with relational philosophies, land-based knowledge, and ancestral wisdom.

1.1. Grammar That Reflects Relationships

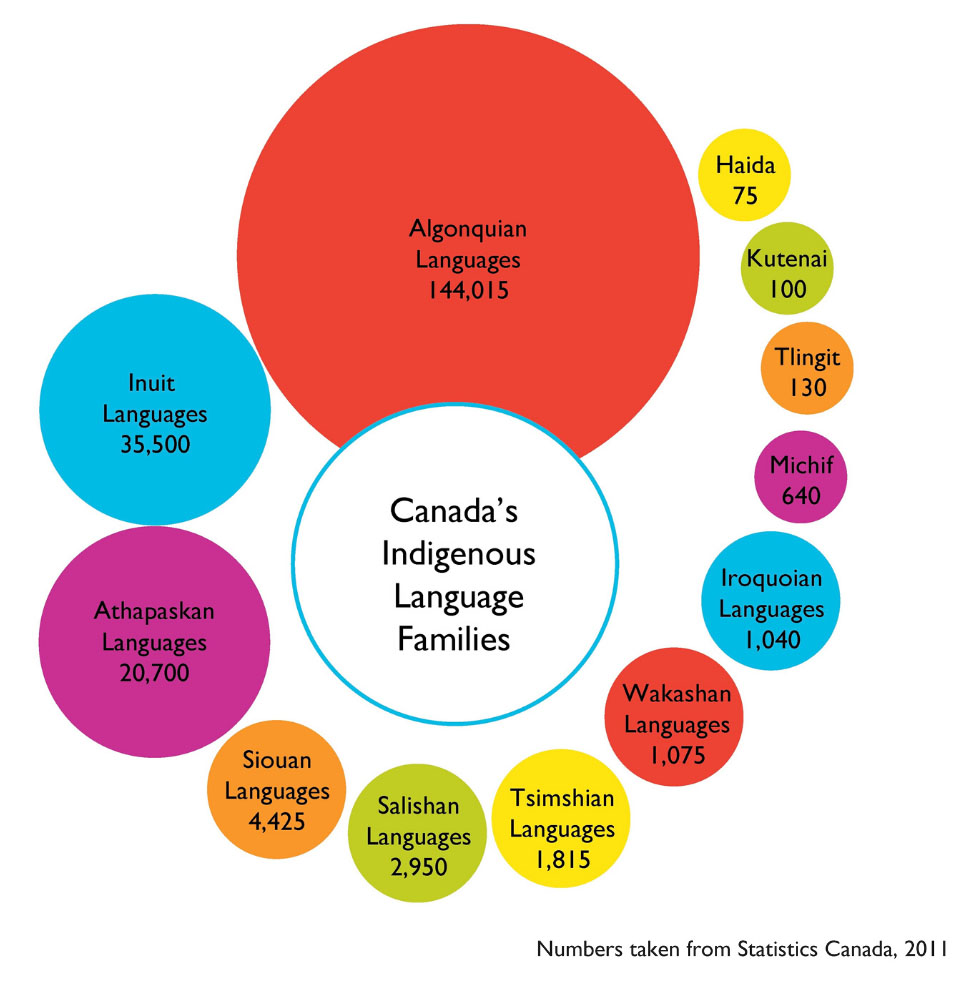

Many Indigenous languages emphasize relationships over objects. For example, in many Algonquian languages, verbs dominate sentence structures, highlighting actions, processes, and interdependence.

In relational languages, identity is not separate from the natural world. It emerges from interaction with people, land, animals, and spirits.

1.2. Words That Contain Cultural Knowledge

Single Indigenous words often hold layers of meaning—ecological, spiritual, and historical. These words cannot be fully translated into English without losing essential context.

Thus, every spoken word becomes a bridge between the speaker and their ancestors, reinforcing cultural identity through daily language use.

2. Language as the Vessel of Culture and Oral Tradition

Indigenous cultures traditionally pass knowledge orally—from Elders to youth, generation to generation. Language is the medium through which stories, songs, ceremonies, and teachings survive.

2.1. Oral Histories and Creation Stories

Creation stories explain not only how the world began but how people should live ethically within it. These stories carry moral lessons, laws, and warnings. When told in the original language, their rhythm and emotional power remain intact.

2.2. Traditional Knowledge and Ecological Wisdom

Indigenous languages contain detailed ecological terminology reflecting deep land-based knowledge—animal behavior, seasonal cycles, plant uses, and more.

This linguistic knowledge forms a core part of Indigenous identity.

2.3. Ceremonial Language

Some Indigenous languages include sacred words used only in ceremony. Cultural practices lose meaning when the language behind them diminishes.

Language keeps culture alive. Without it, cultural identity becomes fragmented.

3. Language as a Marker of Belonging and Community

Identity is both personal and collective. For Indigenous peoples, language is a primary marker of belonging—to a nation, clan, family, and set of responsibilities.

3.1. Nationhood and Membership

Speaking a language often signifies membership in a specific Indigenous nation. It identifies who a person is and where they come from.

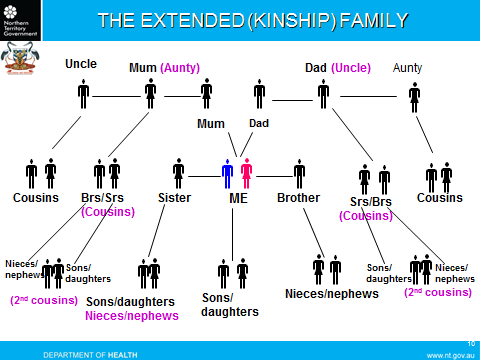

3.2. Identity Through Kinship Terms

Kinship terms define not only relationships but also responsibilities. These cultural identity markers are embedded directly into the language.

3.3. Intergenerational Connection

Language binds generations. When children learn their ancestral language, they can speak with Elders in culturally meaningful ways.

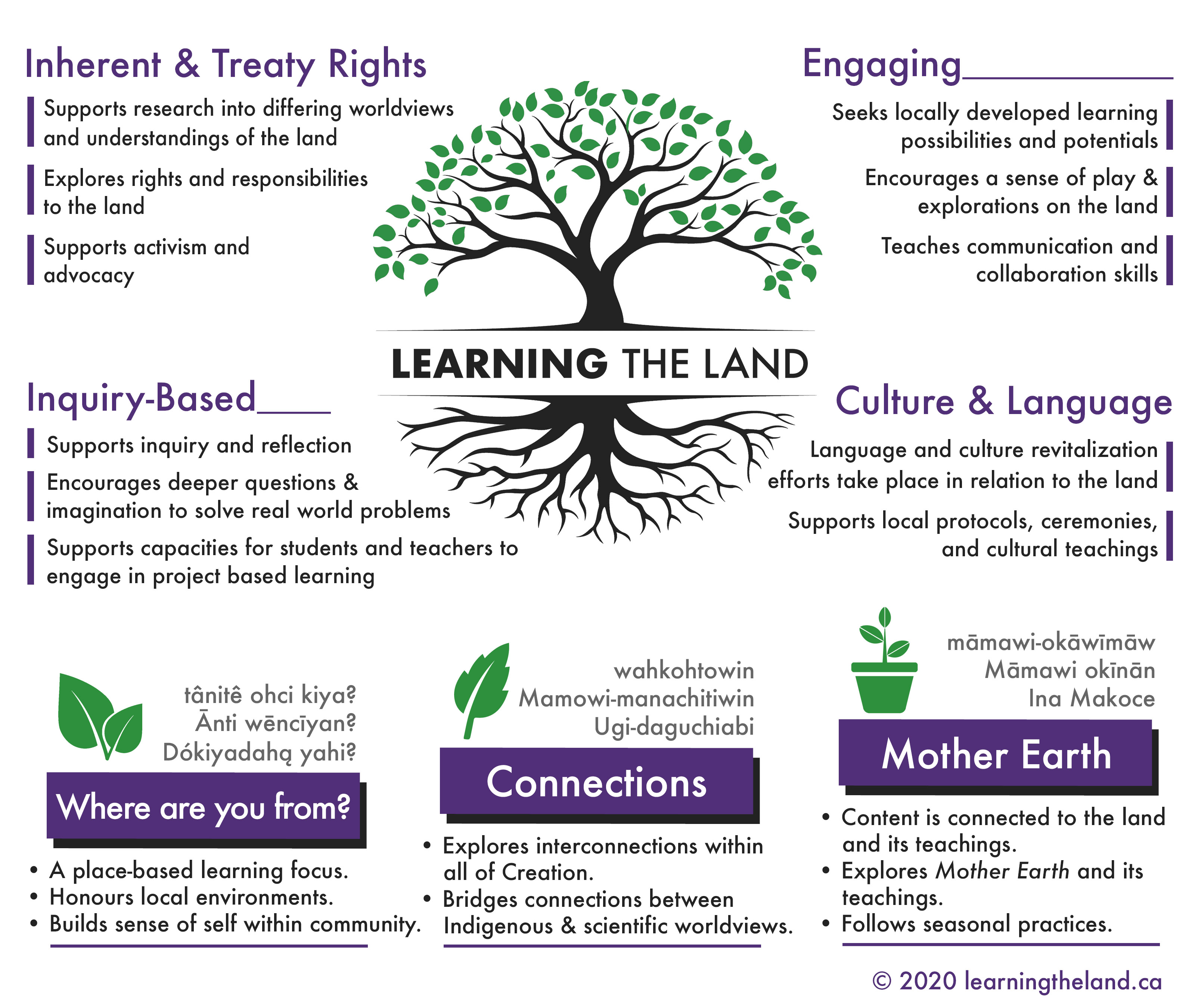

4. Language and Connection to Land

Indigenous identity is deeply rooted in land. Indigenous languages reflect this relationship.

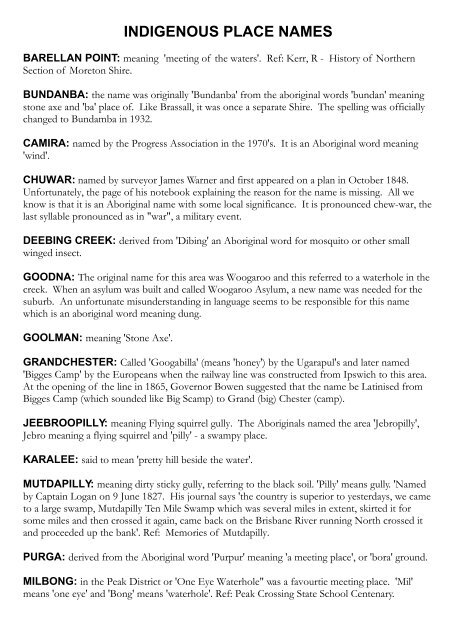

4.1. Place Names as Cultural Maps

Place names often encode ecological knowledge, sacred history, and traditional teachings.

4.2. Ecological Identity

Speaking the language teaches people how to live with the land—not dominate it.

4.3. Land as a Living Relative

Some Indigenous languages use animate grammar for natural features, reflecting beliefs that the land is alive and deserving of respect.

Identity is rooted in reciprocal relationships with the environment.

5. Language Loss and Cultural Trauma

Colonization targeted Indigenous languages systematically. Through residential schools, assimilation policies, and punishments, many communities were prevented from speaking their languages.

5.1. Impact of Residential and Boarding Schools

Children were forbidden to speak their languages and often punished for doing so. This severed intergenerational transmission.

5.2. Intergenerational Trauma

Language loss creates emotional and cultural wounds. Stories, ceremonies, and kinship systems weaken.

5.3. Displacement and Marginalization

Without language, many feel disconnected—neither fitting into colonial society nor fully accessing their ancestral culture.

6. Language Revitalization as Resistance and Healing

Indigenous communities worldwide are leading strong efforts to reclaim their languages.

6.1. Community-Led Revitalization Efforts

Efforts include:

-

language nests

-

immersion schools

-

Elder-youth teaching

-

mobile apps

-

online classes

-

cultural camps

6.2. Healing Through Language

Reconnecting with ancestral language helps people reclaim pride and heal trauma.

6.3. Language as Decolonization

Reclaiming language asserts Indigenous political and cultural sovereignty.

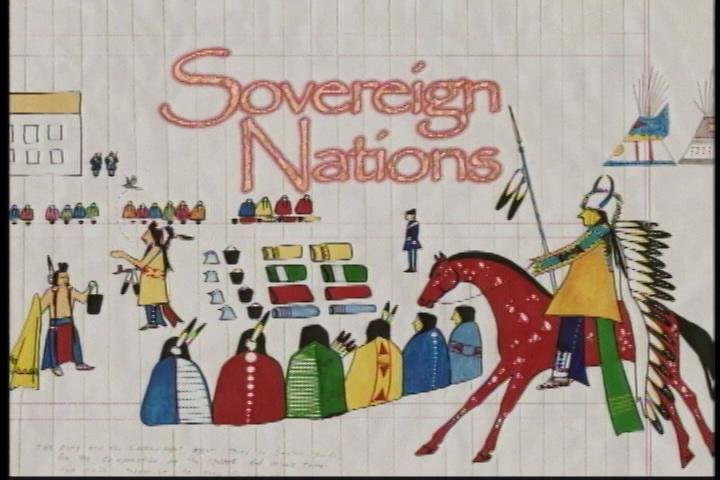

7. Language as Expression of Sovereignty and Nationhood

Language reflects political identity and independence.

7.1. Language in Governance and Education

Many Indigenous-led governments use their languages in meetings, education, and public signage.

7.2. Naming as an Act of Power

Restoring Indigenous place names reclaims identity and historical truth.

7.3. Language Rights

Communities advocate for legal recognition, funding, and language protections.

8. The Future of Indigenous Identity Through Language

The future of Indigenous identity is tied to the future of Indigenous languages.

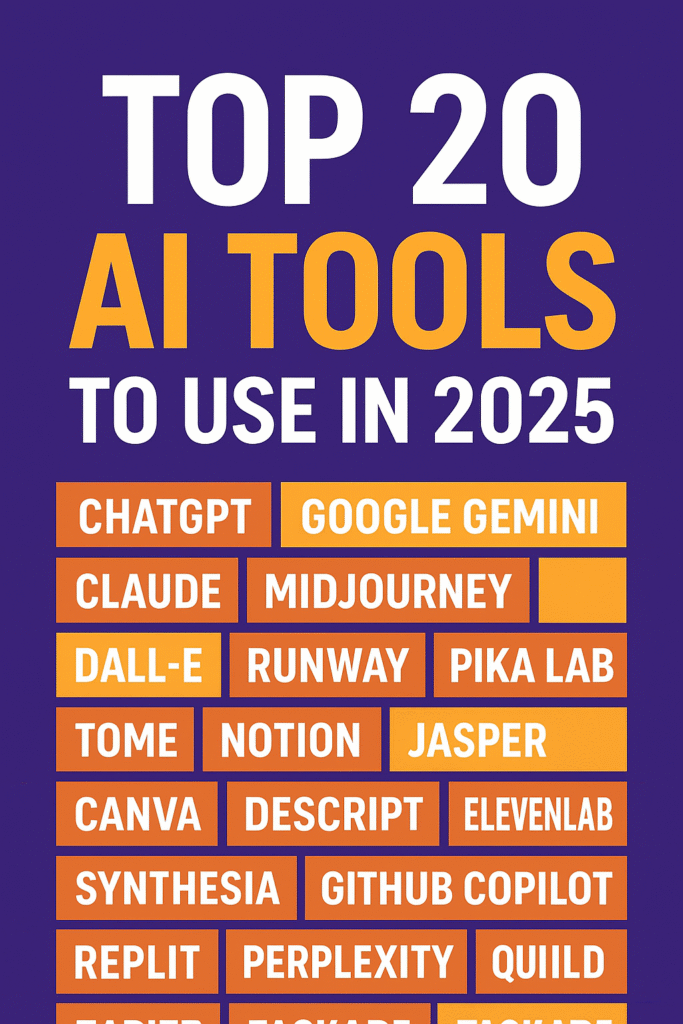

8.1. Technology and Innovation

Apps, podcasts, AI tutors, VR, and online dictionaries help youth learn language in modern ways.

8.2. Strengthening Intergenerational Bonds

Elders and youth learning together strengthens identity and community.

8.3. Identity Reclaimed

More Indigenous people are embracing language learning, reclaiming heritage and cultural pride.

Conclusion

Language is not merely a communication tool. For Indigenous peoples, it is the heartbeat of culture, the memory of ancestors, and the foundation of identity. It shapes worldview, defines community, and strengthens relationships to land. While colonization attempted to extinguish Indigenous languages, revitalization movements are restoring them with power and pride.

To understand Indigenous identity, one must understand the central role of language—a role that will only grow stronger as communities continue reclaiming their voices and their futures.